Materials and Processes

My use of historic techniques and materials stems from my attraction to the materials and forms, my fascination with artisan and craft traditions, my own internalized architectural Eurocentrism, and my disdain for this very attraction to notions of European ideals of beauty.

My role as an artist and maker involves inquiry and contradiction, and the space to play both advocate and critic of what is taking place in the built environment—and how our civic and cultural institutions behave. Through physical acts of making, I intend to act as both advocate and critic of the way in which history has been formed and perpetuated over time—and my hope is to reveal new and unexpected stories in the process.

My current artwork is a critical act of remembering in the present.

Using an historic process allows me to embody the process of remembering, and in so doing, make it relevant to the stories we need to tell today. From Laurajane Smith, “Memory, unlike history, has an intimate relation to the present through the personal and collective actions of remembering.”

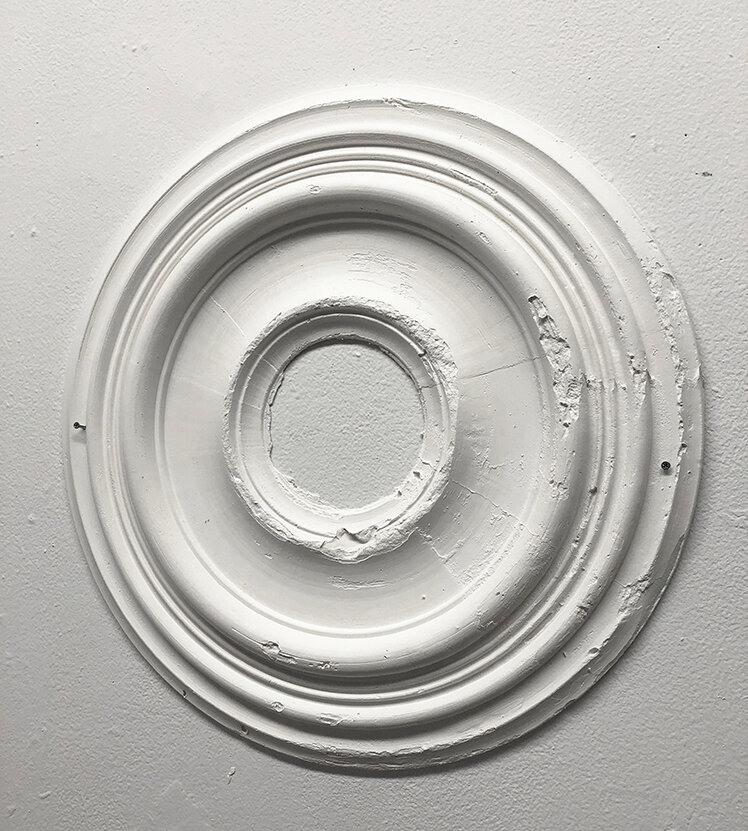

I am interested in how the material properties of plaster can serve as a metaphor for the concept of memory. Plaster is a malleable medium and it goes through a series of state changes—powder, slurry, solid—as it is worked by the craftsperson.

The act of running a decorative moulding takes a precise and sensitive touch, and involves careful timing to run the mouldknife across the plaster at the perfect moment where it will create the mould form instead of destroying it.

I intend my research to be an intellectual pursuit, (with an output that will enhance the discourse around memory, layered history and heritage,) but also physical embodied knowledge gained from working with a material over the course of time.

Problematizing Colonial Ornament

Colonial architecture and its legacy serve to shape the dominant narrative in the United States. Ornamental plasterwork reflects European ideals of beauty, and are representations of beauty, power, erasure, and the malleability of history in their fetishization of classical architectural forms. These displays of power perpetuate the dominant narrative and marginalize the colonized, people of color, and the working class. They are also an important piece of our cultural heritage and reflect Western societies’ love for grandiosity, craftsmanship and history—and were generally built and maintained by the working class and enslaved people. The tension apparent in these seemingly opposing aspects of colonialist architecture is where my inquiry into historic plaster ornament begins.

My work is meant to address the contradictions inherent in the concern for conservancy and cultural heritage, and inhabit the spaces between the issues of loss, preservation, and attractive and repulsive aspects of our history. I intend for my work to address the complexity and layering of history, and how this layering and reinscribing contributes to whose histories and stories get written, and whose go untold, or get erased.

-

Drawing as Curiosity Embodied

According to behavioral economist George Loewenstein, curiosity arises when we feel a “gap between what we know and what we want to know.” This “information gap” is a great motivator for learning.

I teach foundation drawing to students of all ages, and I begin lessons with the reasoning behind WHY we might want to learn to draw. Drawing is curiosity embodied: drawing is learning to see. Learning to draw from observation involves being curious about the world around us and how it looks.

-

Constraints and Creativity

This week I was reflecting on my teaching philosophy (that’s the kind of thing you do when you apply for jobs.) I would describe one part of my teaching philosophy as this:

From the tightest parameters comes the greatest creativity.

A trite adage you might know is “Necessity is the mother of invention.” But many of the best artists know that from a set of rules or constraints, ideas are born.

-

Failure is Informative

Yesterday I spent most of the day making failures. What I had hoped would be an enjoyable studio day of drawing and printmaking turned out to be a little bit frustrating and created no “usable” results.

One thing that’s important to remember is that artists (the ones who consistently try new things,) are always learning to use new materials. What most collectors and viewers don’t see is the painstaking testing that goes on in the studio.